1.5.2

Newsjunkie.net is a resource guide for journalists. We show who's behind the news, and provide tools to help navigate the modern business of information.

Use of Data

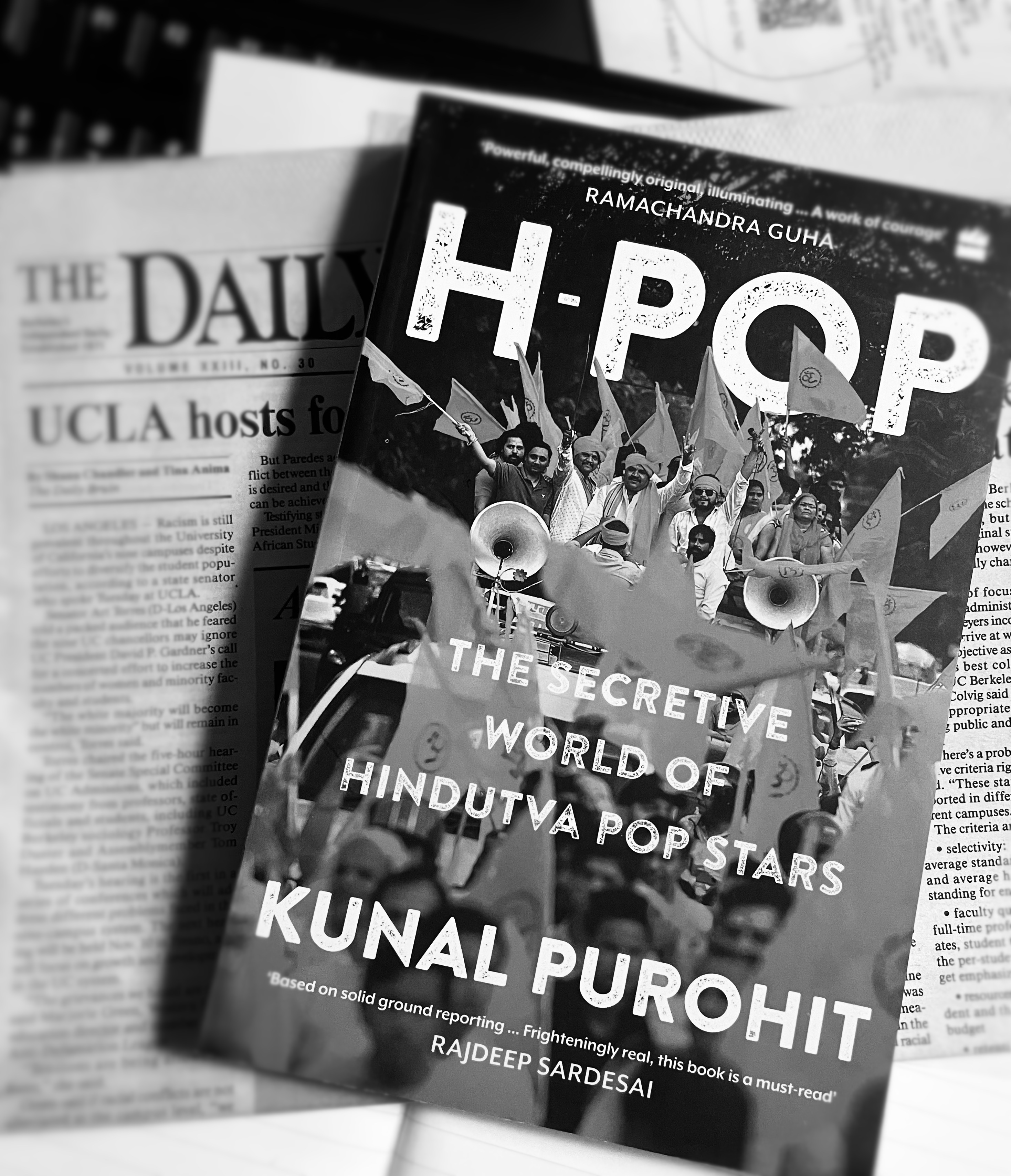

Indian journalist and author Kunal Purohit explores the spread of hate culture in his book H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars (HarperCollins, 2024).

Mr. Purohit gave a presentation on November 19, 2024, at UCLA’s Center for India and South Asia at UCLA; Dr. Anna Morcom, director.

Hindutva is a decades-long cultural/political project to establish Hindu supremacy across India. The ruling Bharatiya Janata party and Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 with an overtly Hindutva platform.

Hindutva Pop, or H-Pop, is popular music, poetry, dance and literature that frames hate speech against Muslims and other minorities as entertainment.

Kunal Purohit contends his research shows H-Pop is spreading beyond its rural origins into metropolitan India, and that the BJP and other Hindutva organizations are co-opting it for their purposes. The book follows the lives of three exponents of the movement: singer Kavi Singh, poet Kamal Agney and publisher Sandeep Deo as they create works with popular appeal that focus hate on non-Hindus.

After the talk, Mr. Purohit sat for an interview with Newsjunkie publisher Gordon J. Whiting.

You use the term everyday hate. How do you define and differentiate this hate from other forms of hate?

With everyday hate, what you get is hate that comes from actors who have no political affiliation, who are not overtly political at all. Nor are they in positions where they're doing what they're doing for a commercial gain or for a gain which is political in nature. These are all people who are leading everyday lives, ordinary lives in jobs like yours or mine. And yet somewhere they're so driven with a sense of anger and hate towards a different community, that they act out on those feelings.

What you get in reaction to that is not big instances of riots between communities. They're not instances of mass killings, as you see in genocides. But there are instances which typically have that one person inflicting a sense of violence on the person of a different community that he or she antagonizes. It could be a word. It could be harsh words that are used express that hate. It could be a form of explicit violence or brutal violence inflicted, or it could be an act of wanting to disenfranchise people on the other side.

It could be asking for their social boycott, getting other people to pledge for their boycott. It is these small acts which never will really make it to the newspaper, which will never really make it to make it to dinner table conversations, because they're not going to travel as wide as a riot can. And yet in those encounters they are extremely powerful and forceful expressions of hate. And that is how I would look at this, this phenomenon of everyday hate.

Would you say the hate has to be activated as it rises and falls? How? What kind of phenomenon is this?

It's laying on a foundation of pre-existing biases and stereotypes. On a constant basis they are reiterated and reinforced, so the person who is holding these biases is facing a continuous sense of radicalization. And this is where H-Pop activates. This is where Hindutva pop culture activates. This is where this constant stream of disinformation that we are seeing in countries like India for the last decade is being able to activate that.

What this radicalization does is it wants you to change the way you look at someone of a different community—in this instance, Muslims. When you look at Muslims, you don't see your fellow human beings. You don't see them as your neighbor. You don't see them as your friend. You see them as someone who is an existential threat to you and your community. You see them as a threat to your sisters, your mother, your wives, and you see them as someone who is out to get you, and this is the sense that gets activated when you're continuously consuming this kind of popular culture.

So would you say Hindutva Pop hardens an existing bias and creates a rationale or opportunity for action, or permission for action?

It does. It looks at people who have an existing sense of bias and prejudice. It seeks to harness and stoke that into a place when those people are driven to express that bias. It constantly gives you a call to action. That's one of the things about Hindutva Pop. It's not just telling you that Muslims are terrible people and it doesn't just tell you that they are existential threats. It will also have a remedy to the situation.

The remedy to the situation can be, at best, calling for a boycott of the community. But at worst, it can be calling for slaughter, for genocide, for an ethnic cleansing of that community. I think that is where it gets extremely potent and extremely dangerous.

In your talk, I did not hear about anti-Hindutva Hindus rising up to stop anything. Is the passivity another form of permission?

That's one of the tragedies of what we're seeing in India today. And I say this a lot: you don't have the Hindus who condemn this sort of pop culture, who condemn this sort of rhetoric, coming out and forcefully expressing their condemnation. You don't have people who distance themselves from this representation of Hindus and and Hinduism.

As a result, this form of Hindu nationalism is the most visible and the most dominant form of representation coming from the Hindu community and that lulls many people to believe that all the Hindus condone this. Which can't be farther from the truth. I know so many good Hindus who will never believe in this. And I would go to the extent of saying that a majority of the Hindus don't believe in this rhetoric.

But unfortunately, we've reached the point where the majority is not speaking out in opposition to this rhetoric, and it's making people believe that maybe all of the Hindus do condone this.

You've put five years into this book, a significant journalistic effort. Given the suspicions that might have been present as you tried to establish rapport with your subjects, what journalistic tools did you use to establish trust?

I was very clear when I decided to write about this, that no matter what my political inclination I would never let that get into the way of getting the story. I knew I was going to be face to face spending a lot of time with people whose political views are so so starkly in contrast with mine, people who I will not be able to see eye to eye with on most issues, people who who are actively expressing their anger and disgust for a different community—something that is anathema to me.

And yet I was certain that I would not let that get into the way of being able to access these people, access and understand their life stories, make them feel comfortable enough to open up to me, and never make them feel like I was sitting in judgment of their work.

Did anyone just walk out and say, I don't trust you?

Thankfully that didn't happen. Before I started the interviews there was one person I was trying to get for the book, and we had a couple of calls. Then she sort of said, "I don't want to be a part of this book." But once I had locked in on all three of (the main) characters, that never happened again till the last day, and I'm very grateful that I was able to get that access, to meet them and spend as much time as I wanted with them.

Now the book is out—are you in touch with them? What do they say about it?

I did send them copies, and I did sort of ensure that they read about it—after the book was published—not before. Of the three people that I've interviewed deeply, two of them thought that the book did a fair job in characterizing them as these people who believe in this this ideology, and these people who will do anything that it takes to promote this ideology.

No PR is bad PR—

No PR is bad PR! Look, I mean, even if the book comes across as a critical retelling of their work, I think we've reached a point in India, where Hindutva ideology and the rhetoric that they spew is the mainstay. It's the mainstream political discourse. So any criticism is only seen as criticism coming from a fringe group of liberals; it's weak, it doesn't matter to the project, because the project is so much bigger, it's not gonna hurt them or delegitimize what they're saying.

Instead, they do realize that books and work like mine are part of a small minority of criticism that comes at them, because what they get on the other other side is vast praise and adulation for what they're doing. So, the third character of the book, the publisher, he didn't enjoy the book because he thought it paints him to be something that he isn't.

I've recounted instances from our experiences together, where he seemed to be very clearly spewing rhetoric against the Muslims. Once the book came out and he read it, he thought it was uncharitable of me to characterize him saying all of those things. He said, I'm not an Islamophobic guy because I know one Muslim, I have a Muslim person in my life. How so? How can I be hitting Muslims?

Good question!

Yeah, good question for sure; but apart from him, the other two felt the book did a fairly decent job at putting their lives in context. Two out of three, not a bad score (laughs).

What advice do you give to journalists attempting to cover hate culture?

What I would like to think is it's now more than ever before that journalists who, no matter what side of the political aisle they’re in, have to go beyond their political beliefs and engage with people who hold extremist views, but who are yet significant enough in number for them to be causing political change.

We're seeing this happen a lot more in the US, in different countries across Europe, and in countries like mine, India, where ideologies that were on the fringe have now come to occupy the mainstream. Journalists need to do much more to engage with these ideologies. They shouldn't be prisoners of their own political beliefs. I think the essence of our times is in being able to understand and analyze, and be able to chronicle ideologies and beliefs and communities which might be very, very different from yours.

So I hope more journalists are able to put their political beliefs aside and engage with these people. Because look, you may not like them, you may not agree with them, but if they are a significant part of the country's population, and if they're causing tectonic changes in the country's political systems, then they need to be engaged with, and they need to be understood more than anything else. So I hope that people do take that message out of this.

Well, you set a shining example. And thank you for spending some time with me.

It's been a pleasure.

Kunal Purohit is an independent Indian journalist. He has reported widely on hate crimes and the rise of Hindu nationalism. Mr. Purohit earned the 2012 Ramnath Goenka Award for Excellence in Civic Journalism. He also received the Statesman Award for Rural Reporting and the UNFPA-Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitive Reporting. His articles have appeared in the Times of India, Foreign Policy, Al Jazeera, ProPublica, Hindustan Times, South China Morning Post, Deutsche Welle and The Wire. He holds an MSc in Development Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. | ||

Source

In-person interview by Gordon J. Whiting, November 19, 2024

Summary keywords

everyday hate, political affiliation, social boycott, pre-existing biases, Hindutva pop culture, radicalization, existential threat, mainstream discourse, journalistic tools, political beliefs, social change, ideological engagement, critical retelling, public perception, media influence

© 2024 Newsjunkie.net

1.5.2

1.5.2