1.5.2

Newsjunkie.net is a resource guide for journalists. We show who's behind the news, and provide tools to help navigate the modern business of information.

Use of Data1.5.2

1.5.2

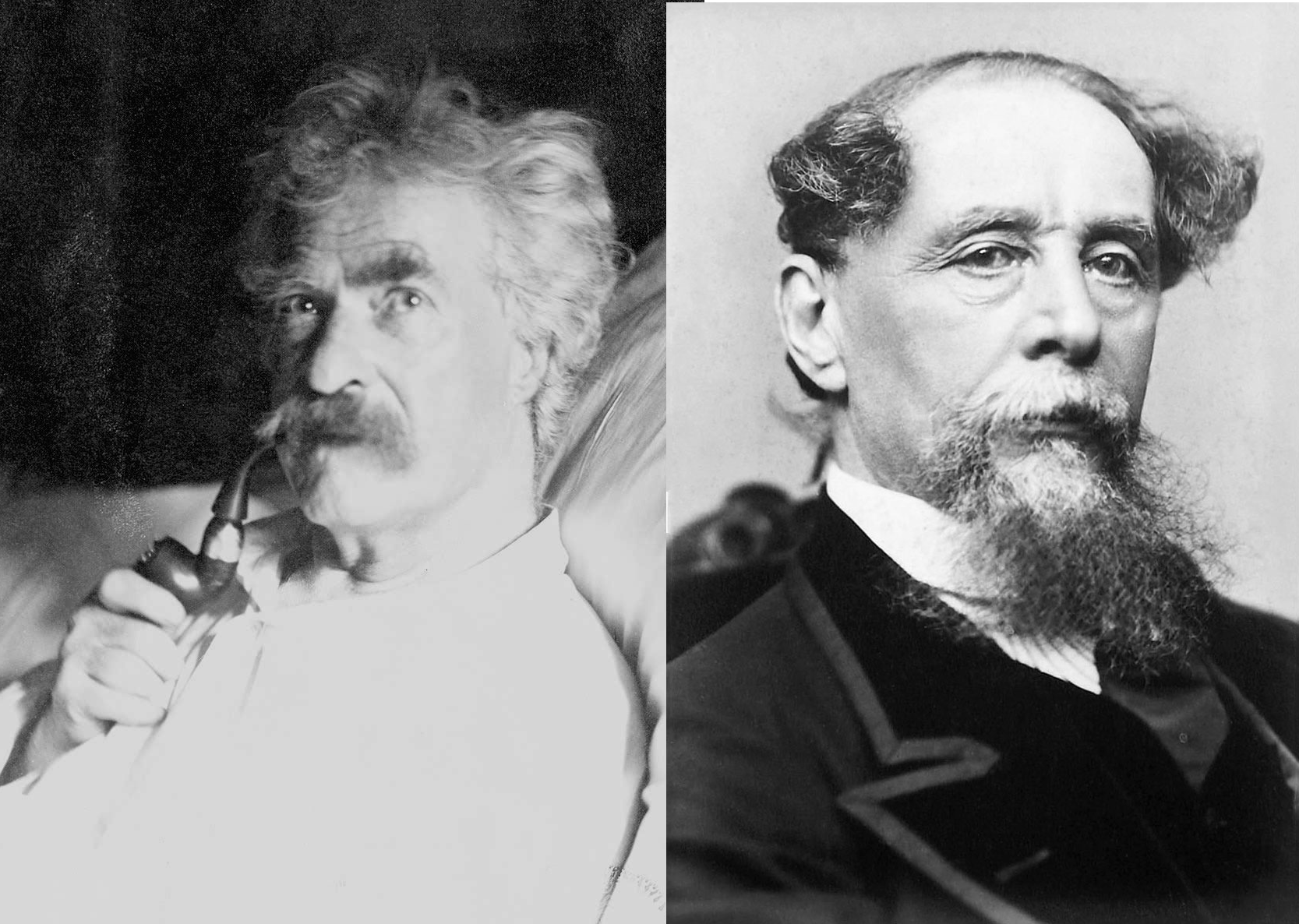

New Journalism isn’t that new. The term originates from the latter half of the last century, but dig further and its roots go back to the great American and British writers, Mark Twain, and Charles Dickens.

These nineteenth-century titans are best known as novelists, but each got their start ink-slinging for the news journals of their time. Mark Twain, born Samuel Clemens, got his pen name working as a journalist. Both writers owe a debt to their reporting days, where they honed their observational skills.

To understand the New Journalism requires a short primer on the traditional expression of the trade.

Twain’s Satiric Voice

New Journalism is famous for using the tools of fiction and applying them to nonfiction. It could have a point of view, rather than being strictly objective. That included humor. Twain excelled at comedy. In The Innocents Abroad, he entertained his audience while skewering his countrymen, oblivious to the cultural and historical significance of the foreign lands they visited.

Twain and Dickens are both famous for their first-person narratives. They weren’t the first to use this literary technique. Ambrose Bierce, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Edgar Allan Poe are all writers of a first-person witness style of journalism. But it was Twain, foremost in American literature, to speak in the vernacular of its people.

Twain described the great deserts of Nevada and silver-mining expeditions, recounts the history of the Mormon migration to Utah, and continued writing about his travels to Hawaii in Roughing It. But his masterpiece, and the source of all modern American literature, according to Ernest Hemingway, is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

No major American novel before it had depicted an enslaved Black character as a fully realized moral center of the story. Such stories weren't found in the broadsheets of that time, and even if they were, they would lack the emotional impact of the novel’s moral climax when Huck believes he will be damned to Hell for helping Jim, but does so anyway because they are friends.

This fictional approach of satire and humor found in Twain’s work has an impact on news reporting that New Journalism was born to tap.

Reporter Dickens

Journalism also birthed one of English’s greatest novelists, Charles Dickens. After a short stint as a solicitor’s clerk, where he learned shorthand, he worked as a political reporter for the Mirror of Parliament. He also conducted parliamentary reporting for The True Sun, a new radical, pro-Whig newspaper published between 1835 and 1838.

His first true foray into literary journalism was a fiction piece, A Dinner at Poplar Walk, published in Monthly Magazine (in existence from 1796 to 1843), which ran in 1833. Writers who contributed to the magazine over its lifespan included William Blake, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

He continued doing parliamentary reporting for The Morning Chronicle, a leading daily political newspaper, eager to scoop The Times, a British national newspaper founded in 1785. (The Times was the first newspaper to use “The Times” in its title, which became a trend in U.S. news publishing.)

Dickens published popular items in Monthly Magazine without pay, but honed his news reporting and writing skills. He became the first editor of a new weekly, Bentley’s Miscellany, while working on his first novel, The Pickwick Papers. It ran as a serial, as did his novel Oliver Twist. He contributed to several other newspapers during this time, and left Bentley’s in 1839.

Reporting informed Dickens’ novels, which explore the conditions of London during the Industrial Revolution with an intimacy that conventional narrative can’t touch. However, work for a variety of publications gave him the experience and skills of a muckraker that he could then apply to the often navel-gazing pages of the traditional novel. It might be a stretch to put Twain and Dickens in the same boat as the new journalists of the 1960s and ‘70s, but they navigated similar seas.

The New School

The seeds of Twain and Dickens blossomed in the hothouse writings of Terry Southern, Truman Capote, Jimmy Breslin, and the other writers who grew from the fertile soil of New Journalism. This style came to fruition between 1963 and 1977.

New Journalism set out to transform reporting by borrowing techniques from fiction to make the prose more vivid, immersive, and emotionally truthful. It sought to capture reality by being less detached and using literary techniques such as scene-by-scene narration, dialogue, point of view, and character development.

While New Journalism wasn’t fully embraced at first, the reverberations can be felt to this day. It rose to prominence at a time when the novel was the height of artistic expression. The new journalists were literally putting themselves in competition with Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Faulkner.

A notable example of this was New York newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin. He’s famous for saying, “I’m the only guy who goes out every day and climbs stairs for a story.” He also didn’t go the traditional route. After John Kennedy was assassinated, Breslin didn’t go to the hospital or seek a quote from the administration, he went to the cemetery to interview the gravedigger; that’s New Journalism.

Kandy-Kolored Wolfe

Tom Wolfe’s mission was to grab readers with his first words and hold them until the last. He was already, in his own words, writing “accurate non-fiction with techniques usually associated with short stories and novels” that could excite readers intellectually and emotionally. Wolfe’s early columns ran to about 1,500 words, but eventually climbed up toward 6,000.

How could he get readers to stay on the article with its lengthy and unorthodox prose style? He wrote in the introduction to The New Journalism (1972), “I’ll use any literary device, and many different kinds simultaneously. I had no hesitation about any device that might conceivably grab the reader’s attention a few seconds longer.”

Understatement was then the norm in journalism, and Wolfe reiterated he would do anything to avoid this recipe for what he considered dull, boring writing.

Wolfe wrote: “The voice of the narrator, in fact, was one of the greatest problems in non-fiction writing. Most non-fiction writers, without knowing it, wrote in a century-old British tradition in which it was understood that the narrator shall assume a calm, cultivated, genteel voice.” Understatement was the thing. “It was a matter of personality, energy, drive, bravura, …style, in a word … the standard non-fiction writer’s voice was like the standard announcer’s voice… a drag, a droning…”

Wolfe’s method, again? Try anything that might work.

He continued: “But the dreamers, aspiring new literary journalists—they would never have guessed for a minute that the work they would do over the next 10 years, as journalists, would wipe out the novel as literature’s main event.”

Southern Exposure

Some journalists thrive on reporting success stories, American Dream tales, feel-good articles, of mighty accomplishments that will stand the test of time and make a nation proud. Terry Southern, a Dallas, Texas, native, and graduate of Northwestern University, and student at the Sorbonne in Paris after WWII, was not one of these.

He gained notoriety as a screenwriter for Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), and the co-author (with Mason Hoffenberg) of the satirical dirty book Candy, which was also adapted for the screen. This led to Esquire, then the epicenter of New Journalism, adding Southern to their masthead.

He was dispatched to Oxford, Mississippi, to write about a summer event at the University of Mississippi campus—a training institute for girls ages six and over who aspired to be majorettes. The summer camp was called the Dixie National Baton Twirling Institute, and drew around 200 girls from the south, desirous of perfecting their baton-twirling abilities, and their individual techniques, while wearing majorette costumes that covered little and exposed a lot.

Mississippi was segregated in 1964. Although the Civil Rights Act had just been passed in 1964, segregation remained entrenched. At the beginning of the article, Southern observes a water fountain labeled “Blacks Only.” He consistently reminds the reader about Jim Crow.

By the time Southern’s sojourn into the deep south was coming to an end, he notes that the experience had not been an especially pleasant one. The reporting was interesting, and the subject matter bordering on the bizarre, but the background of segregated Mississippi (this was his first trip back to the south since he left Texas in 1943), was getting to him—racism was everywhere.

Southern preferred keeping company, and sharing liquid refreshment, with the poor, segregated Black population in Mississippi, to the white racists he encountered throughout his visit to Oxford. While there is no lack of powerful reportage on race relations, and the civil-rights struggle, few pieces can sway a reader like the absurdity of Southern’s New Journalism.

Cold Blooded Capote

It’s no surprise that New Journalism attracted novelists. Truman Capote was already well-known and respected for his novels, and stories, in the elegant, high-prestige New York literary scene. His novella Breakfast at Tiffany's was a critical and commercial success, and was made into a film in 1961 starring Audrey Hepburn.

The gruesome slaughter of a family at their Kansas farmhouse might seem off-topic for Capote, but he was obsessed with the Clutter murders after reading about it in a New York newspaper. He traveled to Kansas, where he was flamboyant and strange to the locals (he arrived wearing a woman’s winter coat), but he could smell the story, and pursued it for many years until it ended with the hanging of Perry Smith, and Richard “Dick” Hickock.

Capote became intrigued with the perpetrators now imprisoned, and established a rapport with Smith. Capote started to view him with a mixture of a kind of sympathy and wonderment, entering the story in a way no traditional reporter would feel comfortable. His obsession with the case, and his relationship with Smith, first published in installments in The New Yorker, eventually led to the publication of In Cold Blood, a groundbreaking book that blurs the line between fiction and non-fiction. Capote called it a “nonfiction novel.”

In Cold Blood was the first true-crime novel in the U.S. to experience widespread success. It took him six years to write the book, as he met with anyone who might be able to add details to the story. The book faced censorship battles, and was banned from a number of high schools in 2001. Critics complained that Capote had formed too intimate a relationship with Smith, who was more of a focus in the book than his partner in the crimes.

Critics also claimed that the book was just a self-promotion project for Capote, who had little care whether the killers were apprehended. Capote is said to have supported their death-sentence appeals in order to buy more time to complete an entire book (their cases went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court). Others complained Capote had succeeded in making sympathetic human subjects out of monsters.

It’s hard to gauge how shocking the book In Cold Blood was at the time of its publication in 1966. Today, true-crime is as mainstream as Cheerios. While not the first to blend literary craft into what would be called New Journalism, it is the defining masterpiece of the genre, and one of the most well-known.

O’Rourke Is Right

New Journalism was born in the maelstrom of the ‘60s, and due to that association, whether rightly or wrongly, is thought of as a left-leaning form. One only has to look at Tom Wolfe to see how foolish it is to pin an ideology to it. Another example would be P.J. O’Rourke.

He came up in the irreverent pages of the sophomoric humor magazine National Lampoon, home of decade-defining satirists such as Michael O’Donohue (Saturday Night Live), and Doug Kenney (Animal House, 1978, and Caddyshack, 1980). He worked his way from contributing writer to editor-in-chief before leaving.

O’Rourke went on to a career in journalism that covered U.S. and world politics. He also wrote many travelogues published in Rolling Stone magazine, and best-selling books, such as Parliament of Whores: A Lone Humorist Attempts to Explain the Entire U.S. Government.

His final book published during his lifetime, A Cry From the Far Middle: Dispatches from a Divided Land, describes his quest to find, and articulate, possible compromises between political extremists on the right, and left.

This is only a partial list, a big toe dipped into a deep well of talent who broadly fell under the umbrella of New Journalism, which also includes Joan Didion, Gay Talese, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson (who we’ll address later), Michael Herr, John Gregory Dunne, John Berendt, and others.

Published December 9, 2025

© 2025 Newsjunkie.net