1.5.2

Newsjunkie.net is a resource guide for journalists. We show who's behind the news, and provide tools to help navigate the modern business of information.

Use of Data1.5.2

1.5.2

At the age of almost nine, I was one of the estimated 73 million people who caught a British rock ’n’ roll quartet called The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show that aired Sunday, February 9, 1964. A record-breaking 60% of Americans watched that evening.

I recall tidbits that characterized the historic occasion: host Sullivan recounting the congratulatory telegram from Elvis and his manager Colonel Tom Parker; the scroll reading “SORRY GIRLS, HE’S MARRIED” under John Lennon’s name that disappointed hopeful teenyboppers; the classy group bow after each song. “You’ve been a fine audience despite severe provocation,” said a playful Sullivan to the screeching, sobbing girl fans writhing in their seats.

Most importantly, I remember the music: it was phenomenal. Divided into two sets, the Liverpool, England, band performed four originals: “All My Loving,” “She Loves You,” “I Saw Her Standing There” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” as well as Meredith Willson’s ballad “Till There Was You” from The Music Man.

And those Lennon-McCartney songs, loaded with insistent melodic hooks, captured the aural heart of their new American fans. Within a year I had a guitar and began learning how to play it. When I wasn’t attached to it like a fifth limb, I had a single ear jammed with an earplug while the Top 40 poured through it via transistor radio (“W-A-Beatle-C!”).

I studied pop music magazines, my faves being Hit Parader (it covered rhythm & blues, folk and country as well as rock and I was intrigued by the range of sounds) and Rave (an English magazine that reported on the other British Invasion bands that I dug like The Rolling Stones, The Who and The Kinks). I wasn’t alone — all over the U.S., U.K. and elsewhere, young people were suddenly learning instruments and starting bands.

It’s now 62 years later and, although they broke up in 1970, The Beatles’ extraordinary power hasn’t diminished. Following 2021’s epic documentary Get Back, filmmaker Peter Jackson’s team, Giles Martin (original record producer George Martin’s son), and others took on a remix of the group’s 1995 autobiographical documentary called The Beatles Anthology. They recut and remastered it and added an additional episode of the three then-living Beatles reminiscing and loosely jamming.

It’s currently streaming on cable channel Disney+. The original six-CD box set of outtakes, alternate takes, and never-released songs called The Beatles Anthology Collection is now eight CDs, and the original documentary’s coffee table book has been reprinted. The book’s text consists of all four Fabs recounting their experience, which was exhilarating, overwhelming, and corrosive in its pressures for the working-class lads from Liverpool. The press coverage has been widespread and mostly—as the young Beatles might colloquially say—FAB! GEAR!

The original strength of The Beatles lay in their innate musicality. Ringo: “I joined the band because they were the best in Liverpool. First and foremost we were musicians.” They spent a couple of years in the early ‘60s getting tight and tough playing seven sets a night in Hamburg dives. While they were rockers at heart, when you’re forced to take requests from drunk tourists night after night, your musical palate broadens.

The Beatles Anthology Collection has their versions of cornball standards like “The Sheik Of Araby” and “Besame Mucho”—a sliver of the non-rockers with which The Beatles learned to satisfy their audiences. George Harrison: “We were just a little dance-hall band.” This became the foundation of the extraordinary breadth of material the band produced later. And as instrumentalists, all four always served the song, even when capable of flashier playing. The melody, lyrics and arrangements dictated what was called for from each Beatle.

Their appeal was further solidified by their aforementioned thrilling three-vocal harmonies. When these were layered on top of potent electric guitars on something like “Paperback Writer,” they kicked ass. Another example is the background harmonies on the savage “Helter Skelter” that helped build a Phil Spector-esque Wall Of Sound. As solo vocalists, both Lennon and McCartney were among rock’s finest. Both could shout with the best of ‘em—Lennon on “Twist and Shout” and McCartney on “Long Tall Sally.” Both were also open-hearted, sensitive balladeers—Lennon on “Julia” and McCartney on “Yesterday.”

Singing Beatles’ songs had become a universal, multi-generational pleasure. I remember in the mid-sixties my sister Julie and I singing two-part harmony on “I’ve Just Seen A Face” as we waited on a sidewalk for our parents to pay a deli bill inside. An older man came out of the deli and stood for a minute listening to us with a huge smile across his face. After he took off, our mother came out excited. “Did you see that man?” she asked. “That was Benny Goodman!” We’d no idea that the legendary clarinetist, bandleader and King Of Swing was our audience that night, but then music is the uber-language, transcending generations.

On August 23, 1966, our mother took sis and I to New York’s Shea Stadium, joining 56,000 others to see The Beatles. While I’m glad I can say I “saw” The Beatles live, I’m not sure I heard them. Even at 11 years of age I knew it wasn’t a musical event, but a spectacle. The blonde teenybopper next to me spent the entire show bawling and squalling “JOOOHHHNNN!!!” It was nearly impossible to dig the music, and while entertaining, it was also disappointing. When the burned-out Fabs soon announced they were quitting the road to concentrate on recording and other endeavors, I understood.

The band began to grow influenced by Bob Dylan and their own ambitions, taking pop music with them on that creative trip. A relatively early song like “I’m A Loser” displayed a lyrical honesty rare in commercial pop music. By their own testimony, The Beatles had been listening to Dylan and their words were becoming more sophisticated.

Combined with the increasing complexity of their record production, they were pushing rock ’n’ roll into new and daring areas. With each album—from 1965’s Rubber Soul to 1966’s Revolver and culminating with 1967’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the band drew proverbial lines in the sand that challenged other musicians to ramp up their musical intelligence.

Rock ’n’ roll was no longer just kiddie music. Eventually it was simply called rock and the best of it equaled the artistic accomplishments of jazz and classical. This was attained by tossing rule books out windows. Paul: “John was a great jumper-off of cliffs. I often remember him saying ‘Look, you’ve come to a cliff. Why don’t you jump off it?’”

Most Beatle fans were utterly delighted. As McCartney said of the ascending orchestration in “A Day In The Life”: “It was very exciting to be doing that instead of twelve-bar blues.” As he later added: “It was a great time for ideas.” George: “In just a matter of months, we’d changed in so many ways that there was no chance of a new record ever being like the previous one.”

The Beatles musical growth mirrored the larger changes in society. George: “That’s what the ‘60s flower power thing was about. ‘Go away you bunch of boring people.’ The whole government, the police, the public—everybody was so boring—and then suddenly people realized they could have fun.” Intellect and the transcending of norms were key to the fun, and they affected the popular art forms of music, film and so on.

As a collective of friends, The Beatles sought this transcendence through musical excellence and succeeded both commercially and artistically, bringing surrealism, Dada and Fluxus art movements, as well as Stockhausen and Ravi Shankar, to pop music. In the process they both reflected and helped to advance the aesthetics of the 1960s and everything that came afterwards.

Despite their acrimonious ending, The Beatles showed that a modest communal experiment—a rock band in their case—could change the world. The bottom line was love.

As John proudly noted, “Nothing will ever break the love we had for each other.” As they sang in “The End” from their final studio work Abbey Road: “The love you take is equal to the love you make.” The world was a better place when there was such a thing as a new Beatle album. While time has now made that impossible, projects like The Beatles Anthology serve as a substitute and do a powerful job of filling the void.

The impact of The Beatles continues to inspire and provide comfort during our current dire period. The band’s enduring popularity and widespread influence give me hope that there are enough of us to ensure that, together, we’ll get back to where we once belonged.

Michael Simmons is a musician and journalist. Creem magazine dubbed him the "father of country punk," for his 1970s work in the band Slewfoot. He's also an activist and filmmaker, has written for Rolling Stone, MOJO, the LA Weekly and the New York Times, and was an editor of the National Lampoon in the 1980s.

© 2026 Newsjunkie.net

All quotes come from the book The Beatles Anthology, published by Chronicle Books, copyright Apple Corps Ltd..

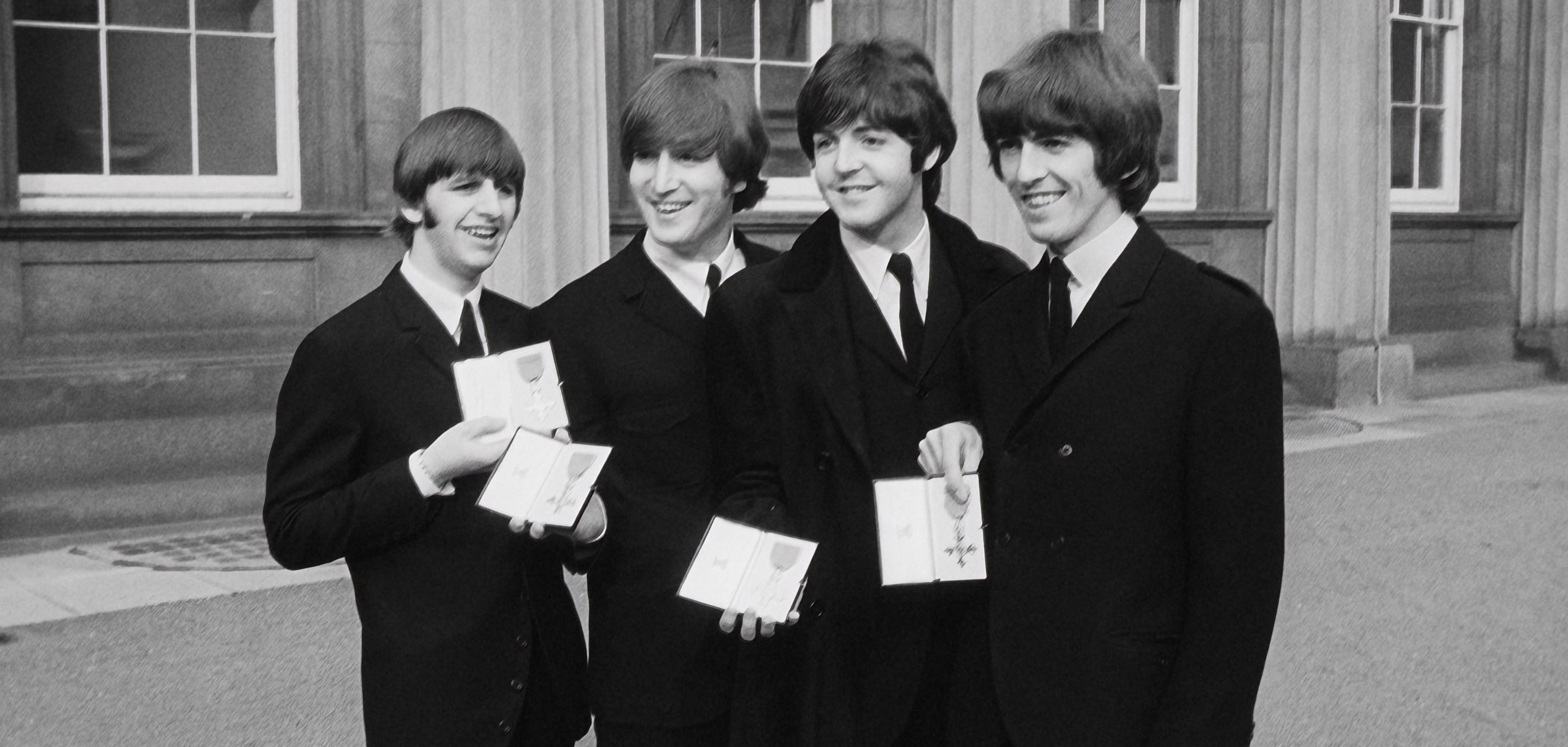

Photo provided by Apple Corps Ltd./Disney+